My team and I have scoped, researched and developed a plan. Now it’s time to bring the rest of the organization up to speed about our new process. But it’s Friday afternoon and no one will read my email, so it’s going on the agenda for our next staff meeting. I pull up the document by searching for its name: Biweekly staff meeting.

I know what you’re thinking: Isn’t twice a week a bit excessive for an all-staff meeting, even one at an organization as small as NTEN? It would be, except that in this case, biweekly means every two weeks. In American English, it means both. Isn’t that confusing? Yes. Isn’t there a perfectly good word that means every two weeks that we could be using instead? Indeed.

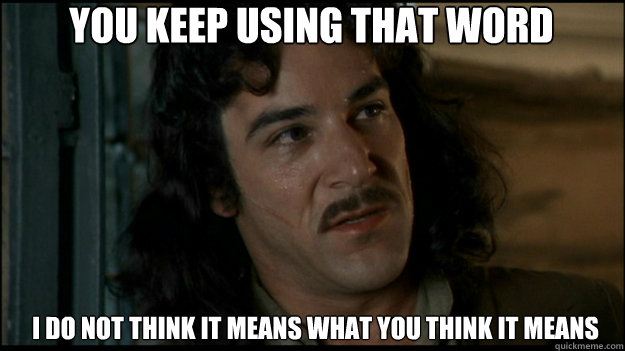

If I could give one thing to America, it would be a gift basket of words it has forgotten it ever had. Because we are failing to use the perfectly good words we have, and we’re using the wrong ones instead. Like Inigo Montoya, I do not think these words mean what you think they mean.

Fortnight

One day, I expect to see an article in the Onion about a study highlighting the steep economic cost of confusion caused by the dual use of the word biweekly: Dinner party embarrassments, planes falling out of the sky after a maintenance crew mistook twice a week for once every two weeks, and gadzooks! All those library fines! It will be satire, of course, but couched in the publication’s inimitable style of speaking truth to the power of our cultural norms. English, as ridiculous as it is, does have a few rules. Chief among them is that a word can’t mean two contradictory things. Fortnight is a perfectly good word. Use it.

Momentarily

When I ask my much-taller husband to fetch me something on a high shelf and he says he’ll do it momentarily, does he mean in a moment or for a moment? Does he mean both? Will I ever know? Well, yes, because he loves me and in a moment, there is a previously unattainable wine glass in my hands. But my point remains: What’s wrong with soon, or “in a moment?” It’s even shorter!

Literally

When the Merriam-Webster dictionary conceded a few years ago that literally had increasingly been used figuratively and therefore deserved a second definition, internet writers figuratively exploded with contempt. While you’ll not find me defending the M-W often (see: its proclamation that mad could be used in place of angry,) I think it was right to add it to the dictionary, but that doesn’t mean you should use it.

Could care less

Oh, but here’s one I was wrong about! Americans adopted the British saying “I couldn’t care less” to convey the same meaning while saying its opposite, something that has always infuriated me because it’s so patently wrong. And incorrect it is, but with reason. Michael Quinion of World Wide Words, who knows about such things, tells us that the phrase crossed the Atlantic in the 1940s and started to catch on in spoken English, though it didn’t appear in print until 1966. And it’s in that spoken version that we find the clues to when and why it cleaved (another word that means its opposite) to its new phrasing. As it turns out, the intonation pattern of “I couldn’t care less” is very different from “I could care less.”

There’s a close link between the stress pattern of I could care less and the kind that appears in certain sarcastic or self-deprecatory phrases that are associated with the Yiddish heritage and (especially) New York Jewish speech. Perhaps the best known is I should be so lucky!, in which the real sense is often “I have no hope of being so lucky”, a closely similar stress pattern with the same sarcastic inversion of meaning.

As Quinion points out, there’s some precedent here in the also-sarcastic “tell me about it!” which is clearly an exclamation rather than invitation. Even though it looks a bit silly when written, the spoken version belies its origins and adds to the rich and complex story of English. So, I learnt something today!